Shoulder Center

The structure of the shoulder

The shoulder is a very complex joint. Strictly speaking, the shoulder consists not of just one joint, but of several joints that work together in a complex way to enable the wide range of motion of the shoulder arm, which we need to "grasp" our environment. This places high demands on the structures involved in the construction of the shoulder, because the shoulder joint is unique in its function. With the shoulder, we are able to accelerate a handball to more than 100 km/h, for example, and then perform highly sensitive tasks with our arm the next moment.

01

The glenohumeral joint: This is the joint between the humeral head and the glenoid cavity of the shoulder blade.

02

The acromioclavicular joint: The acromioclavicular joint formed by the acromion and the clavicle.

03

The sternoclavicular joint: The joint between the collarbone and the breastbone (sternum).

04

The scapulothoracic gliding surface: A not immediately recognizable joint between the shoulder blade and the back of the chest (thorax).

You must have the Adobe Flash Player installed to view this player.

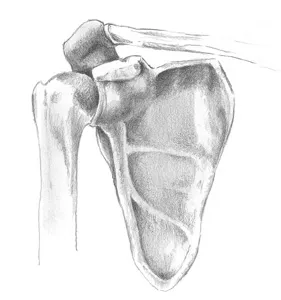

The aforementioned joints must function optimally together to enable the arm's range of motion. However, this construction is not sufficient. The glenohumeral joint, also known as the main shoulder joint, has a unique structure compared to other joints in the human body. The labrum-glenoid socket is very small compared to the humeral head. This socket is only attached to the side of the glenoid cavity and is not enclosed by it.

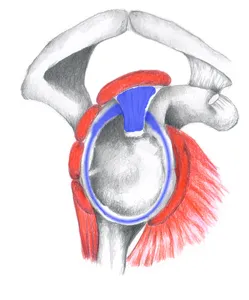

This means there is no bony guidance for the joint. To prevent the humeral head from dislocating, the socket is enlarged by a labrum. A connective tissue lip surrounds the bony rim of the socket, enlarging the socket and holding the head in the socket through adhesive forces. The image on the left shows the shoulder socket viewed from the side, with the glenoid labrum marked in blue.

The insertion of the long biceps tendon emerges from this labrum at the upper edge of the socket. The long biceps tendon then runs from this point over the humeral head and later bends 90 degrees downwards into the sulcus bicipitalis, a canal at the anterior border of the humeral head.

You must have the Adobe Flash Player installed to view this player.

But even this joint lip is not sufficient to adequately stabilize the glenohumeral joint. Other stabilizers in the shoulder include the joint capsule, which completely surrounds the joint and, in a sense, seals it off, preventing synovial fluid from escaping. More important than this joint capsule, however, are the deep shoulder muscles, the so-called rotator cuff. The four muscles that combine to form the rotator cuff surround the joint on all sides and provide muscular stabilization. This muscular stabilization is also primarily responsible for the support of the shoulder joint. For this reason, the shoulder is also referred to as a muscularly controlled joint.

Which muscles belong to the rotator cuff?

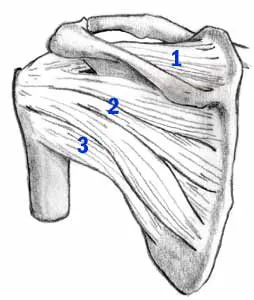

The rotator cuff is a complex of four muscles that join together with their tendons at the humeral head, almost completely enclosing it. For this reason, it is also referred to as a cuff. If you look at the shoulder from the front, you can see two muscles that belong to the rotator cuff. The subsapularis muscle sits flat on the front side of the shoulder blade and, with its tendon, extends to the anterior humeral head. This muscle is primarily responsible for internally rotating the arm (Fig. right, no. 2).

Visible above and marked with the number 1 is the supraspinatus muscle. This muscle originates from the posterior surface of the shoulder blade and runs between the acromion and the humeral head, attaching to the top and outside of the humeral head. The supraspinatus is primarily responsible for raising the arm laterally. Its course between the acromion and the humeral head can cause it to become squeezed during various movements. This can lead to inflammation of the tendon. This is then referred to as impingement syndrome.

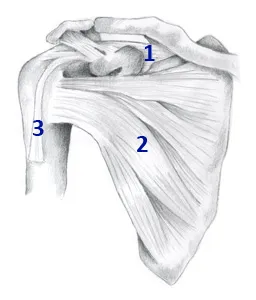

The image on the left shows the shoulder blade from behind. Here, too, the supraspinatus and its course beneath the acromion are clearly visible. Below this are the infraspinatus (No. 2, image on the left) and the teres minor (No. 3, image on the left). Both muscles originate from the posterior surface of the shoulder blade and pull on the posterior humeral head. Due to their position and course, they are responsible for the external rotation of the upper arm.

All of these muscles together work in a well-balanced relationship to one another, ensuring that the humeral head is optimally centered in the socket. If this balance is lost, for example, due to excessive training of a muscle, the humeral head can deviate from its optimal position. This leads to shoulder pain, such as the so-called "Non-Outlet Impingement Syndrome".