Shoulder Center Saar

Frozen shoulder

Frozen shoulder is a distinct condition that leads to stiffening of the shoulder joint. In addition to the term "frozen shoulder," there are numerous other terms that largely describe the same condition, such as frozen shoulder, painful frozen shoulder, adhesive capsular stiffness, adhesive capsular fibrosis, and adhesive capsulitis, to name just a few. Frozen shoulder is characterized by a painful, increasing restriction of movement in the shoulder joint.

For patients, frozen shoulder is a condition with alarming consequences. Frequent episodes of severe pain, especially with sudden movements, and an often rapidly increasing loss of shoulder function significantly impact their quality of life. My daily consultations with many patients seeking a second, third, or even fourth opinion document the despair. Various unsuccessful, more or less aggressive, attempts at therapy are extremely stressful.

Below I present the current scientific findings and my own experiences from treating more than 4,000 patients.

What are the symptoms of frozen shoulder?

Shoulder stiffness usually begins gradually. Initially, patients only notice nonspecific pain during certain movements, such as reaching backward in a car or attempting to tuck their arm into a jacket sleeve. This pain increases over time. Initially, shoulder pain is the main symptom. Restrictions in movement often go unnoticed. Later, stiffness of the shoulder joint, which gives the disease its name, develops. The severity can vary greatly; it is not uncommon for the joint between the humeral head and the glenoid (socket of the shoulder blade) to eventually become completely stiff.

However, since the shoulder blade remains mobile, those affected can usually compensate for a large part of the stiffness. The frequent night pain can be very disturbing and significantly reduces quality of life. One of the most important symptoms in the early stages of the disease is the shooting pain during sudden movements.

What causes the condition of frozen shoulder?

There are many triggers for frozen shoulder. Accidents with prolonged immobilization of the joint or even severe wear and tear can lead to shoulder stiffening.

In the majority of cases, however, frozen shoulder is "idiopathic" in nature. This means that the actual trigger is unknown or no causal reason for the stiffening can be identified.

People with metabolic disorders are more likely to suffer from frozen shoulder. These include, for example, diabetes mellitus (diabetes) or patients with thyroid disorders and lipid metabolism disorders.

Frozen shoulders are particularly common in diseases of the cervical spine, such as degenerative cervical spine syndrome (painful wear and tear of the cervical spine). Furthermore, patients with Dupuytren's disease of the hands are more likely to experience frozen shoulders.

All painful shoulder conditions, such as calcific tendonitis, impingement syndrome, or rotator cuff tears, can lead to shoulder stiffness due to pain.

However, there are also many cases where no trigger or connection to another condition can be found. The exact cause in all of these cases remains unclear.

Over the past six years, we have treated more than 4,000 patients with this condition (as of March 2024). This large number of cases allows us to conduct our own scientific research on this condition. Compared to many other studies that only cover a few hundred cases, we have access to over 4,000 cases.

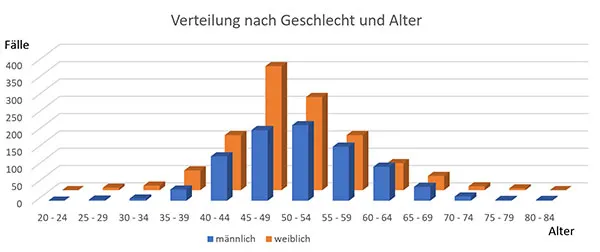

Statistical analysis of patient age and gender has shown that frozen shoulder occurs primarily between the ages of 45 and 60. Women are slightly more frequently affected than men.

What is the course of the frozen shoulder disease?

Frozen shoulder disease usually progresses through three stages.

In the first phase, called the initial or inflammatory phase, the primary symptom is increasing pain in the shoulder joint. The symptoms often begin spontaneously or due to an identifiable trigger. As symptoms progress, pain also occurs at rest and, especially, at night.

In the second phase, also known as the stiffening phase, the symptoms often slowly subside. At this point, there is an increasing restriction of movement in the shoulder joint. This is often not even noticed at first because the arm is still being protected due to the symptoms. However, external rotation and abduction of the arm in particular are often already significantly restricted. Subsequently, the mobility for internal rotation and raising the arm forward also becomes less effective. Since the stiffening can initially be compensated for by shoulder blade mobility, it is not uncommon for patients to see a doctor due to pain and not yet fully aware of their almost completely stiff shoulder joint.

In the third and final phase, mobility improves. Pain is minimal or nonexistent during this phase. Gradually, mobility in the shoulder joint returns. However, it is impossible to predict with certainty whether full mobility will be achieved as before the onset of the disease.

It is impossible to predict with any certainty how long the disease will progress, and especially when the third "healing stage" will be reached. The course of the disease varies greatly. Some patients show a significant improvement in shoulder mobility after approximately one year of the onset of the disease. Others show only a slight improvement in mobility even after 36 months.

The course of the disease can of course be positively influenced and shortened through special therapy.

The total time taken by these phases of shoulder stiffness—i.e., initial, stiffening, and thawing—vary considerably from individual to individual. Some patients complete the entire process within 12 months, while a number of patients with shoulder stiffness may need up to 36 months.

How does the doctor diagnose frozen shoulder?

Already during the patient's conversation, an experienced physician can obtain many clues to the diagnosis of shoulder stiffness. Observing the patient's movements while undressing for further examination can also lead to a suspected diagnosis of shoulder stiffness.

During the examination, the limited mobility of the shoulder joint is assessed. It is important that the doctor fixates the shoulder blade to the chest to eliminate compensatory movements and mechanisms. This is the only way to determine the complete limitation of movement of the joint between the humeral head and the shoulder blade (glenohumeral joint). To differentiate frozen shoulder from other shoulder joint conditions, we have used two tests that have proven effective: the inferior glide test and the sudden pain test.

Imaging procedures such as shoulder ultrasound (shoulder sonography) are primarily used to rule out other causes of restricted shoulder movement, such as infection or a ruptured shoulder tendon. Our experience has shown that in primary or idiopathic frozen shoulder, ultrasound often reveals virtually unremarkable findings similar to those seen in a healthy person.

The X-ray, which should also be taken, primarily serves to rule out advanced wear and tear or other more serious conditions. In idiopathic frozen shoulder, this image is also usually unremarkable. After the ultrasound examination by an experienced examiner and the X-ray, the correct diagnosis is usually already made. Thanks to the use of modern, high-resolution ultrasound systems, magnetic resonance imaging, which was often routinely performed in the past, can often be omitted. Only in cases of doubtful findings in previous examinations is magnetic resonance imaging important for ruling out more serious conditions such as bone tumors. In idiopathic frozen shoulder, magnetic resonance imaging also does not reveal any changes consistent with the disease. The diagnosis is therefore primarily made based on the limitations in mobility typical of the disease, the medical history, and the almost complete absence of changes in the imaging.

How is shoulder stiffness treated?

Even today, frozen shoulder remains a condition whose treatment raises many questions. Some of what I report is already scientifically proven; others, admittedly, are based on my expert opinion, based on more than 4,000 frozen shoulder patients treated over the past 12 years.

Before recommending any therapy, it's important to remember that we're treating a metabolic disorder and only secondarily a mechanical problem caused by it. The disease itself is benign and has an excellent self-healing rate of over 80%, although it requires a great deal of patience.

As a result, there are various therapies that either don't promise success or carry a high, sometimes excessive, risk. Below is a list of therapies that I cannot recommend or can only recommend with reservations:

Shock wave therapy:

It is not known whether shock waves can normalize impaired collagen metabolism. The pain experienced during treatment can exacerbate the symptoms.

Surgical removal of a bone spur, reaming of the shoulder roof or removal of the bursa:

None of the operations mentioned above leads to increased mobility of the shoulder or is able to positively influence the disturbed collagen metabolism.

Anesthetic mobilization or the forcible movement of the shoulder under anesthesia:

This procedure results in uncontrolled shoulder injuries. Bone fractures and tendon ruptures are frequently documented injuries, and in my opinion, the success rate is disproportionate to the complication rate.

Medications for treating frozen shoulder:

Currently, no medications are known that can quickly cure this condition. Cortisone, which I will discuss later, holds a special position.

Physiotherapy or physical therapy:

This is certainly the most difficult and controversial topic. The fact is that even intensive physical therapy with multiple treatment sessions per week (3-5 per week) is not able to prevent shoulder stiffening. I have seen hundreds of patients who received intensive physical therapy for months and performed the exercises they had learned with great dedication. Nevertheless, complete shoulder stiffening occurred.

Why is that?

Even with this therapy, it is often forgotten that we are treating a metabolic disorder. Physiotherapy has no effect on impaired collagen metabolism.

No one would think of trying to cure other metabolic disorders, such as thyroid dysfunction or diabetes, with physical therapy. My own experience has shown that physical therapy can also be counterproductive.

If pain is repeatedly triggered during treatment by maximum stretching, improved mobility occurs immediately after the treatment. However, this success is only short-term. During subsequent stretches, pain usually increases, and mobility decreases even faster.

When patients tell me about treatments involving stretching to the limit of pain and almost unbearable pain during the treatment, I can only shake my head.

The positive effect of physical therapy described in every literature is, in my view, limited to a

The shoulder, or rather the glenohumeral joint (joint between the humeral head and the socket), should not be viewed in isolation. Even if only this joint stiffens, the adjacent structures are also affected, such as the cervical and thoracic spine and the shoulder blade with its surrounding muscles.

While targeted treatment of these structures only leads to a slight improvement in mobility, it can improve quality of life and thus has a "feel-good factor." Pain during treatment should be avoided.

Unfortunately, the list of proven successful therapies is small. Here are the treatment options that I consider to be sensible.

As already mentioned, cortisone has a positive effect on the clinical picture.

Cortisone injections often lead to relief of symptoms. Injections directly into the joint, in particular, lead to a significant reduction. Unfortunately, the effect is often short-lived.

However, such cortisone injections are not without risk and should only be administered rarely.

Oral cortisone administration carries a lower risk. A study was published several years ago recommending a step-by-step cortisone therapy with tablets.

We have been using this step-by-step cortisone regimen to treat frozen shoulder for years. Our own experience with it is mixed.

Through treatment, we almost always achieve a significant improvement in pain. In particular, patients report being able to sleep at night again, which significantly improves their quality of life. Improved mobility is also often reported. This appears to be due to the phenomenon that movement causes less pain.

Our own post-treatment examinations rarely show objectively improved mobility.

After the positive effects of cortisone were also reported at the San Diego Shoulder Course in 2018, we modified our previous regimen. If there are no contraindications to cortisone and the patient is suffering accordingly, I recommend this modified cortisone gradual regimen:

Starting with approximately 0.5 mg per kg of body weight, prednisolone is taken in the morning for 5 days, after which the dose is reduced by 0.125 mg of prednisolone per kg of body weight every 5 days.

Prescribed are 20mg prednisolone tablets which can be cut into quarters.

The individual doses must be rounded up or down.

At the end of this regimen, I administer a dose of 5mg prednisolone for 20 days before discontinuing it completely.

This results in the following dosage for a patient with a body weight of 80 kg:

Cortisone step-by-step plan modified by Dr. Groß

| 5 days | 40 mg prednisolone | 2 tab. |

| 5 days | 30 mg prednisolone | 1 1/2 tab. |

| 5 days | 20 mg prednisolone | 1 table |

| 5 days | 10 mg prednisolone | 1/2 tab. |

| 20 days | 5 mg prednisolone | 1/4 tab. |

As already reported, the frequently performed surgical therapies such as bone spur removal or reaming of the acromion are useless.

Instead, the Americans recommend a capsulotomy.

During this procedure, which is performed as part of an arthroscopic procedure, the joint capsule in the front and lower parts of the joint is surgically loosened and partially removed. Even with this procedure, the underlying metabolic disorder cannot be treated. However, the altered capsule is removed, restoring shoulder mobility. However, there is a risk that impaired collagen synthesis may persist, causing the shoulder to stiffen again. Furthermore, the surgical procedure is not without risks.

In the USA, this operation is still widely promoted, even though experts there emphasize that the condition usually heals on its own with patience.

The reason for recommending the procedure anyway is the impatience of Americans, which can be explained by a different social system and the economic losses that the individual suffers in case of illness.

I, like most of my colleagues, are very hesitant about the surgical procedure, especially since we can't guarantee that the stiffness won't recur.

In summary, treatment primarily involves comprehensively informing the patient about the harmlessness of the condition. If there are no contraindications and the patient is suffering accordingly, I recommend cortisone administration. Only in cases of extreme symptoms and long-term, unsuccessful conservative treatment should I consider surgical capsulotomy.